Retail leaders wrestle with a deceptively simple question:

“Is this store or market performing as well as it should be?”

The problem is that most organizations still answer that question by looking at performance in isolation. Rankings, averages, and year-over-year growth get used as proxies for success. That works until it does not.

A top performing store may simply have better structural advantages such as stronger trade area demand, less competition, higher traffic visibility, or more favorable demographics. A struggling store may actually be doing a great job given its market reality. When leaders miss that distinction, they risk making the wrong decisions about coaching, investment, pricing, and expansion.

This is where performance relative to potential matters.

The leadership problem

Most retail organizations face the same challenges.

- Store and market performance varies widely.

- Operators or local leaders ask, “Why can’t we be like the top performers?”

- Corporate teams struggle to explain what is realistically achievable.

- Decisions get made based on rankings instead of context.

The result is frustration on both sides. Leaders feel they lack clarity. Operators feel they are being compared unfairly. Analytics teams get stuck defending numbers instead of driving action.

Why assessing potential matters

Assessing performance relative to potential allows leaders to answer three critical questions.

- What should this store or market realistically be capable of?

- Is underperformance driven by structure or execution?

- Where should we invest time, effort, and capital for the biggest return?

When done well, this shifts conversations from judgment to diagnosis. It also creates a common language across pricing, operations, marketing, and growth teams.

The key is not starting with the most sophisticated solution. It is starting with something credible, usable, and capable of maturing over time.

Three practical approaches to assessing retail potential

These approaches are not mutually exclusive. Most organizations use more than one as their data and capabilities evolve.

Step 1. Simple benchmarking and gap sizing

Why leaders use it

This is the fastest way to understand where performance differences exist and where attention is needed.

How it works

- Choose a primary performance metric. For example, sales, profit, or throughput.

- Rank or group stores and markets on that metric.

- Compare stores to market averages or top performers.

- Size the gap between actual performance and benchmarks.

What you need

- Core performance data.

- Basic reporting and analytics skills.

Pros

- Fast to implement.

- Easy to explain.

- Highlights obvious gaps quickly.

Cons

- Still largely descriptive rather than explanatory.

- Peer definitions can be subjective and debated.

- Still need to isolate drivers of performance.

This approach often unlocks better conversations without requiring advanced analytics.

Step 2. Peer-based benchmarking

Why leaders use it

Leaders want fairer comparisons that reflect real world differences between stores and markets.

How it works

- Identify a small set of structural factors. For example store size, format, urban vs suburban, competitive density.

- Group stores and markets into similar peer sets.

- Benchmark performance within each peer group.

- Define realistic stretch targets based on top performers in each group.

What you need

- Core performance data.

- Some descriptive market or store context.

- Strong business judgment.

Pros

- More credible comparisons for operators.

- Reduces noise from structural differences.

- Makes improvement targets feel achievable.

Cons

- Still largely descriptive rather than explanatory.

- Peer definitions can be subjective and debated.

- Does not clearly separate structural limits from execution issues.

This approach often unlocks better conversations without requiring advanced analytics.

Step 3. Performance-to-potential modeling

Why leaders use it

At scale, leaders need a consistent way to estimate what each store or market should be delivering given its context.

How it works

- Identify key structural drivers of performance. For example demographics, competition, access, format.

- Build a model that estimates expected performance.

- Compare actual results to expected results.

- Use the gap as a signal of over or underperformance.

What you need

- Broader internal and external data.

- Modeling capability.

- Strong interpretation and storytelling skills.

Pros

- Explanatory and causal.

- Fair and defensible comparisons.

- Scales well once trusted.

Cons

- Higher data and skill requirements.

- Dependent on available data, with some drivers of performance inevitably remaining unseen.

- Requires more explanation for understanding.

This approach works best when positioned as a benchmark, not a crystal ball.

A simple way to compare the three approaches

| Approach | What it answers | Data and skills needed | Best used when | Key trade-off |

| Simple benchmarking | Where are the biggest gaps? | Core performance data; basic BI | Early stage or quick diagnostics | Lacks context and clear actions |

| Peer-based benchmarking | How do similar stores perform? | Performance data plus light context | Credibility with operators matters | Still descriptive, not causal |

| Performance-to-potential modeling | Are results above or below expectation? | Broader data and modeling skills | Scale, fairness, and precision matter | Higher lift and explanation needed |

Turning gaps into explanations using decomposition

Identifying gaps is only half the job. Leaders also need to explain them.

This is where gap decomposition becomes powerful.

Once you know a store is underperforming relative to potential, you can break the gap into understandable components such as:

- Price and mix effects.

- Traffic and throughput effects.

- Operational constraints.

- Local execution choices.

Many organizations already use waterfall charts in pricing and finance to explain changes over time. The same logic applies here.

Instead of saying, “This store is underperforming,” you can say:

- x% of the gap is driven by lower average transaction value.

- y% is driven by lower traffic.

- z% is operational and may require local intervention.

This transforms analytics from a scorecard into a coaching tool.

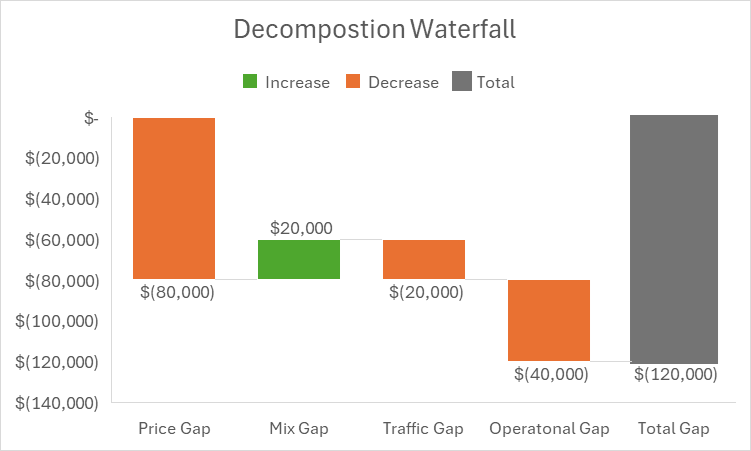

A simple decomposition waterfall example

Imagine a store is delivering $120K less in annual sales than expected for its market.

That gap can be explained by each component and then visualized in a waterfall:

Instead of a single red flag, leaders now have a clear, structured explanation of where performance is leaking and which levers are most likely to matter.

A final thought for leaders

At Solvenna, we see performance-to-potential as a leadership capability, not just an analytics exercise. The most effective organizations start with simple, credible benchmarks, layer in context where it matters most, and selectively apply advanced methods when the data and teams are ready.

The goal is not perfection. It is progress that leaders and operators trust.

Start simple. Be honest about data and skill constraints. Design a framework that gets smarter over time without changing the story every six months.

When leaders assess performance relative to potential, decisions get clearer, conversations get healthier, and investments get smarter.

Where Solvenna Comes In

Solvenna helps retail and consumer brands move beyond rankings and averages by assessing performance relative to potential. We work with leadership, analytics, and operations teams to identify why performance varies, translate gaps into clear actionable explanations, and focus attention on the levers that actually matter without overengineering the solution.